For most of human history, male strength—physical, moral, and situational—wasn’t a personality trait; it was a social responsibility. Men were expected to stand the post, take the hit, and keep watch so others could sleep. In the Natural Man framework, that’s the Protector at work: the man who brings order to chaos and safety to...

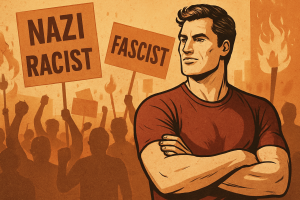

When the Mob Decides You’re a Villain

When society turns disagreement into a death sentence, modern men scramble to hide, apologize, and conform, but it never saves them. The Natural Man stands firm because his roles—Protector, Provider, Pioneer—don’t change with the mob’s mood. He doesn’t seek approval to live out his purpose, which is why he remains steady while others collapse.